Oscars pt. 1: Who Should've Won Anyway?

- Ryan C. Tittle

- Mar 1, 2024

- 8 min read

At one time, the Oscars were my Super Bowl. As young as sixth grade, I would watch them and dream of my own shining moment when I would receive the golden statue and I would give a speech and be played off by the orchestra. Then, movies changed and I changed. I can’t say I’ve watched the Oscars for a while now, but I know what they’re about, how they work, how films get nominated and win.

My screenwriting and film professor Steven Bach was an Academy Award-voter, even breaking privilege by showing Oscar screeners in our American Film History class at Bennington. That’s where I first saw Million Dollar Baby, one of Clint Eastwood’s emotion manipulators (like Mystic River). Bach was frank about the Oscars, He told us when an actor directs a picture, they invariably win Best Director because any other actor dreaming of directing will want to win someday. And, as actors comprise the bulk of Oscar voters, there’s kind of a, “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” thing going on. For the sound categories, Steven would vote for any animated film (“They have to come up with the sounds all from scratch.”) Clearly, he knew nothing about sound design, but his vote still counted.

And therein you have the problem with most award ceremonies. It is an industry patting itself on the back. But Oscars don’t count for nothing. Once you win or are nominated, they use that to death in your billing in future trailers and it’s something no one can take away from you. So, from an industry standpoint, they’re important. Why they have, since the 1970s, become a platform for actor-activists who win to lecture the American public, I’ll never know and is a discussion for a later time. (But I have to say, since we’re here, why Joaquin Phoenix’ win for Joker prompted him to rail at the cattle industry will haunt me till my dying day).

At any rate, they are part sham and part pageant and can make or break careers, so if you’re interested in movies, they’re important to pay attention to. This week, I’ll look at winners for Best Picture that were clearly the wrong choice from a historical vantage point. I’ll concentrate on the latter half of the twentieth century because the twentieth century I understand. What in hell’s going on in the new millennium is anyone’s guess.

Next week, despite seeing only a smattering of the films nominated, I’ll present my wagers on who will win at the big ceremony. I’ve never been that keen an Oscar seer, but I’ve guessed correctly every President of the United States since I’ve been voting (why haven’t I made money on it?), so I’ll throw my two cents in and see if they land on heads or tails.

The 1950s

All About Eve is, for some, a perfect comedy—tautly written, superbly acted. For me, it’s a bit of a bore. While Father of the Bride might have been a sentimental nominee in 1950, clearly Sunset Boulevard, directed and co-written by Billy Wilder, was the film of record that year. Meta before there was such a thing, Wilder’s exploration of a silent starlet driven to a disreputable state when the talkies came in is pertinent now more than ever. If one look only at how women are treated in the industry en masse, it is easy to see that Sunset provides more than a meta-neo-noir, but a comment upon an industry famous for exploitation followed by excommunication.

Amazingly, An American in Paris won over Elia Kazan’s bullet-proof adaptation of Tennesee Williams’ play A Streetcar Named Desire—a film perhaps hampered by the censorship of the time but has withstood as a monument to what acting could be. The fact that Marlon Brando was a revelation is no surprise but should be reiterated—he is the greatest American actor to appear in film. I would rather see him slur his words than Gene Kelly dance once a day and twice on Sundays.

It is widely regarded that Cecil B. DeMille’s win for The Greatest Show on Earth, an ode to circuses, is one of the great blunders in Academy Award history. After all, it was up against Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon, a Western one studies in order to craft a great Western.

The 29th Academy Awards chose an adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days over Giant, one of only three films that captured James Dean’s undeniable greatness, a seamless adaptation of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I (a perfect musical), and DeMille’s remake of The Ten Commandments, which still impresses to this day.

The 1960s

That Robert Wise and Jerome Robbin’s film version of West Side Story is brilliant is in no doubt (as much as Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner’s version is a veritable turd), but when placed against Judgement at Nuremberg, there is no contest. If half the actors who’ve ever worked in film could pull off what Maximillian Schell did, the decision would have been obvious, not just for its subject matter (the Shoah), but for its profound power that lingers with us still.

Of course, hindsight is 20/20. And the Oscars are what they are: a popularity contest. But 1966, the year where the studios began to crumble, it is not hard to see that the choice of A Man for All Seasons (a play that only makes sense in the context of the time) could lose to an adaptation of a play that remains with us and is as vibrant as ever—Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—Mike Nichols’ first, but not only, masterpiece.

1967, however, was an impossible year. Nichols’ The Graduate, Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, and the eventual winner, Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night are neck and neck in importance, though for different reasons. The Graduate was a hot commodity from which an introspective kind of filmmaking emerged, In the Heat of the Night sated Hollywood’s taste to denounce racism, but Bonnie and Clyde ushered in what, for me, is the silver age of cinema—and perhaps the greatest era. For those of you who read the blog, you know my favorite moment in film history begins with Bonnie and Clyde and ends with Jaws, which was brilliant, but destroyed small, personal films. Ah, well. Nothing is meant to last forever. Still, Jewison’s film will always be interesting for sociologists and Bonnie and Clyde will be the film that changed the industry. Should it not have been Best Picture?

The 1970s

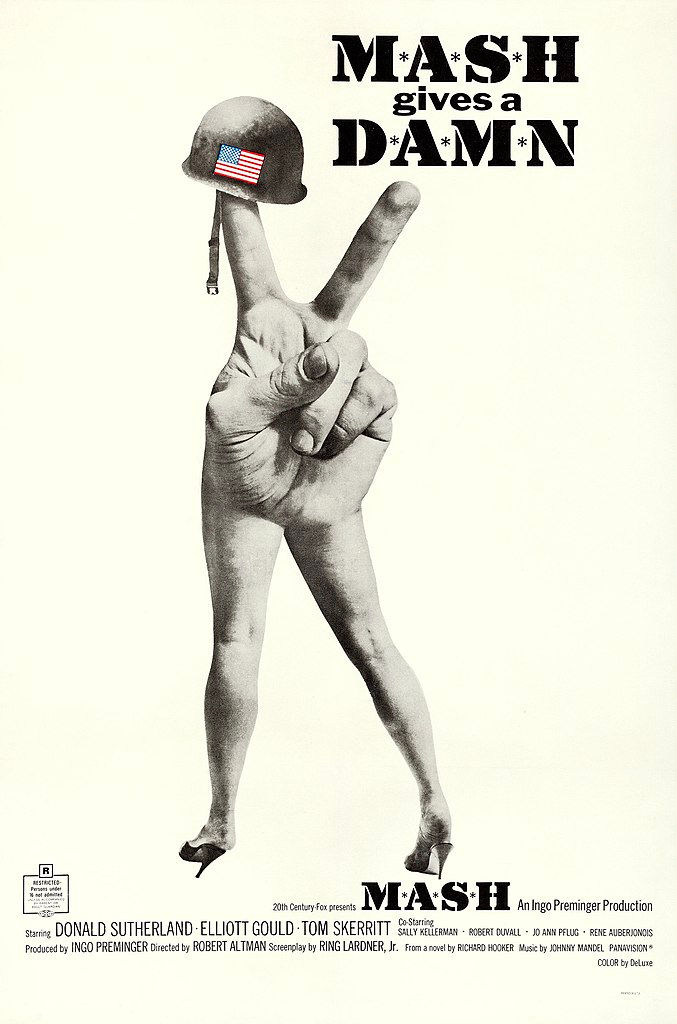

While Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces served as a starting point for Jack Nicholson to be taken seriously, one performance does not a best picture make. In 1970, two important war films were on the table: Patton and M*A*S*H. Which one would you rather watch now, knowing the ultimate pointlessness of war?

The following year provided even more abundance of talent. William Friedkin’s The French Connection won and that seems well deserved—except that it was up against Stanley Kubrick’s perfect adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange, Peter Bogdanovich’s breakthrough with The Last Picture Show, and Jewison’s remarkable adaptation of the Bock and Harnick musical Fiddler on the Roof. Musicals were in decline, so Fiddler had no shot. Kubrick’s film, of course, was much too controversial. Friedkin’s choice was a smart one for the time, but Clockwork (like most of Kubrick’s films) will be the one on repeat.

I know this will be an unpopular opinion. Though it entered the world with mixed reviews, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part II has somehow come to be regarded as great or better than its predecessor. Neither statements are true and, as much as people may not want to hear it in light of present-day inquisitions, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is still the benchmark for a certain kind of gritty picture—sadly lost to time now.

The bicentennial year provided much for the Academy to contemplate. Perhaps, because of the political climate of the time, it made sense to award Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky hero to the world rather than All the President’s Men, a film that showed the corruption deep at the heart of our floundering nation. Network too, in its way, was a prophecy, but I suppose most people think Martin Scorcese’s Taxi Driver should have won as it is an important film from an important filmmaker. While that may be the case, the prequel to Joker was in itself a sick joke and Scorcese has more than redeemed himself with better movies, decade after decade.

The last year of the 70s, indeed, would have been a quandary for any voter. Peter Yates’ brilliant Breaking Away was possibly seen as too small a film to win Best Picture. Norma Rae most certainly would have won an award if the Peoples’ Choice Award was a thing at the time. But Copolla’s Apocalypse Now is the only film of consequence these many years later. Kramer vs. Kramer, though well-acted, well-written, and well-directed pales in comparison to the greatest thing to come out of the Vietnam experience: a film that told its story in a poetic rather than propagandistic voice.

The 1980s

Beginning with Robert Redford’s Ordinary People, the shot at actors-cum-directors winning the prize shot up astronomically. Redford, however, has never developed as a filmmaker, producing overly long, turgid films with just enough commercial potential to sweep their deficiencies under the rug. Every film nominated that year was better. Film buffs will say it should have been Raging Bull. I would probably fight for David Lynch’s The Elephant Man, and even more would, perhaps, have given the prize to Coal Miner’s Daughter, a blueprint for a perfect biopic.

Often a film that is truly deserving of a Best Picture win will settle for a win or nomination in the Best Screenplay field. This is, perhaps, why most filmmakers are screenwriters themselves—so they can win an award every once in a while although they know their film won’t win first place. Such was the case in 1982 when Sir Richard Attenborough’s long and hagiographic Ghandi trumped Sidney Lumet’s impeccable Paul Newman vehicle The Verdict. David Mamet was nominated for Best Screenplay, and should have won, but instead a biopic trumped a legal drama. Provenance over professionalism personified.

The last decade of the 1980s brought on, perhaps, one of the most egregious errors in Oscar history. Spike Lee’s magnificent Do the Right Thing was not even nominated for Best Picture. It was nominated for Best Screenplay (as most of the greatest films do) but lost even that to Tom Schulman’s treacly script for Dead Poets Society. Driving Miss Daisy is a competent film when placed against others of its kind, but it is no Do the Right Thing. Eschewing Lee’s obvious belief that racial matters titled the selection, Alfred Uhry has as much right to say what he feels about the subject as does Lee. But the best film did not win. When all the copies of Driving Miss Daisy are lost to time, there will always be Do the Right Thing.

The 1990s

Redford’s trend continued in the first year of the ‘90s when Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves won over Scorcese’s Goodfellas (a better example of what Scorcese can do than Taxi Driver ever was). Wolves is a good film, but I’ve seen Goodfelllas, I’ve watched Goodfellas, Goodfellas is a friend of mine and, Dances with Wolves, you’re no Goodfellas.

I have gone back and forth over my love-hate relationship with Robert Zemeckis’ Forrest Gump. On the one hand, I’m an Alabamian and when I first saw the film, I thought Gump was a real person and I was proud of him, idiot savant that he was. But to say it was, overall, a better film than Quention Tarantion’s Pulp Fiction (the screenplay, another Oscar winner), would be a lie. In some ways, Gump tells the story of the 20th century in digestible bites that serve to remind as much as to sugarcoat the horrors of that century. Pulp Fiction will outlive it by a hundred years with nothing more than its sheer creativity.

For the most part, I think (of the one’s nominated), the rest deserved their laurels. What do I care? Who gives a flip? That’s for you to decide. If I were an Academy voter, my voice would be heard and, if you’ve disagreed with any of my sentiments, you are welcome to your opinion. What counts are the tallied votes. And, no matter what promises the Academy has made, the vast majority of voters will be older, more traditional than the average bear, and their vote will no doubt bring backlash.

Which brings us to square one. Yes, these awards affect careers (in good ways, like Tarantino; in bad ways, like Halle Berry). But they are unimportant in the grand scheme. Do not be like me and pine for the chance at your Oscar speech. Seek out greatness from wherever spring it might emerge, and have your own Best Picture to rely upon in times of strife.

Comments