David Henry Hwang, pt 1: More Than M. Butterfly

- Ryan C. Tittle

- May 12, 2023

- 22 min read

Updated: May 22, 2023

For the next few weeks, in honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I will celebrate my mentor and teacher David Henry Hwang and his impressive body of work. In the winters of 2001 and 2002, I served as David’s intern in New York City. It was my first trip to the Big Apple and David was generous with his time in taking me to meetings, introducing me to other playwrights, taking me to my first Broadway and Off-Broadway shows, and talking with me endlessly about his career (he’s been my favorite playwright since age 11 and I’m proud to say I reminded him of a ten-minute play he had completely forgotten he had written!).

He gave of his time even as he was raising two small children. I will forever be grateful for the experience. He even invited me to the Broadway premiere of his revision of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, II’s Flower Drum Song. Taking into account his generosity, dedication to mentoring young writers, and his position (I believe) as our greatest living playwright—let’s just say it was an honor and one of the highlights of my life. This week, I’ll take a look at his non-musical plays, next week his work in musical theatre and opera (he is the most performed living opera librettist), and the next his adventures in Hollywood.

I first published a long-form version of this profile in my collection Everyone Else is Wrong (And You Know It).

David Henry Hwang is a playwright, screenwriter, and librettist from Los Angeles, California. He wrote the plays Kung Fu, Chinglish, Yellow Face, Tibet Through the Red Box (adapted from Peter Sis’ book), Golden Child, Face Value, M. Butterfly, Rich Relations, Family Devotions, and FOB as well as the short plays Cain and Abel, A Very DNA Reunion, The Great Helmsman, Jade Flowerpots and Bound Feet, Merchandising, Bang Kok, Trying to Find Chinatown, Bondage, As the Crow Flies, The Sound of a Voice, The House of Sleeping Beauties (adapted from Yasunari Kawabata’s novella House of the Sleeping Beauties), and The Dance and the Railroad. Along with Stephan Müller, he created a new version of Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt. He was educated at the Yale School of Drama and Stanford University. He lives in New York City.

*****

Something was happening in California in the late 1970s that was akin to the Civil Rights Movement of the late ‘60s. Budding Asian American consciousness had hit college campuses. Groups formed to begin examining the meaning of being from Asian descent in the melting pot of America where Caucasians were becoming a plurality rather than a majority. At Stanford University, a young Chinese American student named David Henry Hwang was beginning to discover the power of the theatre while playing in pit orchestras for musicals and studying with novelist John L’Hereux. These two elements collided at the perfect time for Hwang to complete a play called FOB (from the term “Fresh Off the Boat”) that took elements of Chinese folk tales and opera and clashed them with a story of young ABC (“American Born Chinese”) in L. A. The play, in metaphor and spirit, dramatized the feeling of “otherness” in one’s own country.

Hwang has since risen to prominence as the preeminent Asian American playwright, being the first person of Asian descent to win the Tony Award for Best Play and opening the professional New York theatre to the stories of Asian Americans that groups like the East West Players and playwrights like Frank Chin had been telling out West. He is a writer who tells culturally specific stories in universal and unique ways and who has a keen interest in diversifying his craft into many different forms. He has forged an inspiring career that is as unique as his take on this country and its diverse inhabitants.

As mentioned above, Hwang’s first play was FOB. The Stanford Asian American Theatre Project produced the first staging of the piece at the Okada House Dormitory in 1979 while Hwang was still a student. He was encouraged to send the play to the Eugene O’Neill Playwrights Conference in Waterford, Connecticut. Many playwrights, such as August Wilson and Christopher Durang had to submit several times before the Conference took the bait, but Hwang’s FOB was snatched up quickly and developed at the Center shortly thereafter. The famed producer Joseph Papp (who had brought Hair and outdoor Shakespeare to New York) saw the play and found a place for it as his Public Theatre. This success at such a young age was due not only to the freshness of the material, but the fact that it brought a subject to the theatre that was largely unknown to East Coast theatre audiences.

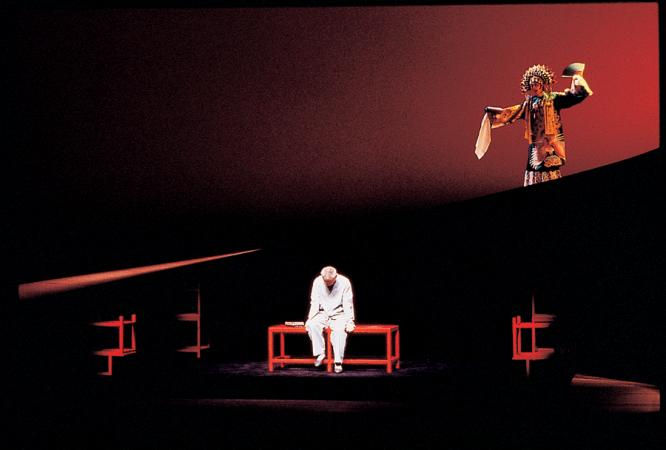

The play premiered at the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1980 under the direction of the legendary actor/director Mako, who assembled a fresh young cast that included the graceful and talented John Lone (who had been trained in the Peking Opera) and Tzi Ma, an equally talented and familiar face (if not name) in Hollywood. The New York Times drama critic Frank Rich, the so-called “Butcher of Broadway,” went Off-Broadway to examine the talents of this new voice. Over the next decade, Rich would be Hwang’s most fervent supporter.

FOB most assuredly is the first play to read for those interested in Asian American theatre, along with Chin’s The Year of the Dragon. All the concerns, frustrations, and the glories of the immigrant/assimilation experience were found in its monologues, vignettes, and a stunning finale where the Peking Opera and American Broadway-style comedy melded together. The play won an Obie Award for Best American Play and was quickly anthologized in “Best Of” Books. It would also begin a relationship between Hwang, Papp, and Rich that would be beneficial to establishing Hwang’s assured place among the important playwrights of his generation.

Hwang’s next project, as he left L. A. for life in New York, was to be a children’s play commissioned by the New Federal Theatre. The simple, elegant language and small-scale theatrical power of the piece was retained, but The Dance and the Railroad emerged as another powerful, important work of the Chinese American experience for adults. The story concerns two Chinese railroad “coolie” laborers in the middle part of the nineteenth century. This historical drama included another combination of American theatre and the Chinese opera—the lead role written for and given the name of Lone.

Through long, aria-like monologues and hilarious two-person scenes, the play pits a worker who is at strike with the rest of the coolies (Ma—a part written for the FOB actor) encountering a worker who chooses the strike as time to practice the art of the opera. Ma challenges Lone to teach him the art and he becomes a dedicated student as the strike is eventually won. Lone also directed the piece and choreographed the opera movements for the show, which had its professional premiere (again at the Public) in 1981.

In his Times review, Rich wrote a glowing introduction for Hwang, calling him “a true original:” “A native of Los Angeles, born to immigrant parents, he has one foot on each side of a cultural divide. He knows America—its vernacular, its social landscape, its theatrical traditions. He knows the same about China. In his plays, he manages to mix both of these conflicting cultures until he arrives at a style that is wholly his own…By at once bringing West and East into conflict and unity, this playwright has found the perfect means to dramatize both the pain and humor of the immigrant experience.”

The Dance and the Railroad was a Drama Desk for Outstanding Play nominee. The play has often confused the author that it has been so honored as it is such a (on-the-surface) simple play. But it contains Hwang’s voice, on full display with its quirky humor and poetic passages that make the simple seem deeply profound. Also, its look at the experience of the Asian American from a historical perspective prepared Hwang for more versatility in his works. Lone and Ma’s performance was recorded for a television version of the play (directed by Emile Ardolino), which aired on what is now A&E. This production won a CINE (Council on International Nontheatrical Events) Golden Eagle Award and has sadly never been given a home-video release.

Hwang refers to his first three stage works as his “Trilogy on Chinese America” and as part of his “isolationist-nationalist” phase. His most critical, serious, and disturbing work of this early period was Family Devotions, the final play of this trilogy. The play concerns three generations of an Asian American family living in a wealthy suburb of L. A. Two elderly women—Ama and Popo—are at the delicious comic center of the first act. But, more than any work before it, Hwang’s play becomes deadly and frightening in the second act as Di-Gou—a relative from China’s mainland—returns and is forced to participate in the Evangelical Christian devotions of his family. This play also opened in 1981 at the Public under the direction of Robert Allan Ackerman, who had directed FOB at the O’Neill Center. The play featured the largest cast of Hwang’s up to that point and an ensemble was created featuring several actors who have become beloved character actors: Michael Paul Chan, Jodi Long, Lauren Tom , and Victor Wong.

This production was also nominated for a Drama Desk Award. Rich commented in the Times that “[t]his playwright crossbreeds sassy, contemporary American comedy with the gripping, mythological stylization of...[Asian]...theater—ending up with a work that remains true to its specific roots even as it speaks to a far wider audience” and called the play “Hwang's funniest play to date. His farcical premise is pure Kaufman and Hart.” Family Devotions deals seriously with the dangers of forcing Western religion on people of other backgrounds yet remains hilariously funny. While a black comedy, its final moments are also some of the most dramatically effective in Hwang’s canon.

He would then set out to do something else entirely. His next few plays would branch out from the Chinese American experience and look at other cultures and became a test of his versatility. He did not venture far from Asia for his next two projects—a pair of one-acts that were based on the folktales and films of Japan. Hwang had become pessimistic about relationships between men and women—his first wife, the artist Ophelia Y. M. Chong, and he would separate shortly before the success of M. Butterfly—and his new plays would highlight both the mutual distrust and intense curiosity that plagues relationships between men and women.

He turned first to adaptation as a source of inspiration. The Nobel Prize-winning writer Yasunari Kawabata had written a novella called House of the Sleeping Beauties, which his friend and supporter Yukio Mishima called “an esoteric masterpiece.” It told the story of old Eguchi and his visit to a mysterious brothel where seemingly comatose women simply sleep next to visiting customers, without engaging in sex. Hwang decided to write a play about how Kawabata might have come to write such a story. Kawabata is the central figure as he investigates a brothel he has heard about from his friend (Eguchi) and it also features Kawabata in his moment of death (though a fictional version).

The second play was more somber and sparer than The House of Sleeping Beauties and had less of a focus on language and more on the silence between words. The Sound of a Voice is a historical story about a samurai who stumbles upon the house of a woman rumored to be a witch. The plays went nicely together and were produced as a single evening’s entertainment, under the title Sound and Beauty, again at the Public in 1983.

It would be Hwang’s last theatrical project with Lone, who directed both plays and performed the role of the Man in The Sound of a Voice. Sleeping Beauties again featured Wong, who played the role of Kawabata. Mystifyingly, the plays earned Hwang his first negative reviews. Rich called the show an “earnest, considered experiment furthering an exceptional young writer’s process of growth,” but found both shorts contrived and less mature than Hwang’s previous work. Still, the plays didn’t incite Rich’s normal ire as it was apparent he found this writer special.

Both works, I believe, show the writer at his best. Critics often have trouble with writers changing direction if they’re on a roll, but Hwang has admitted there have been few very good productions of the two plays. Sleeping Beauties features lines of aching (not to put too fine a point on it) beauty and a touching death scene. Also, an early scene of the two characters playing a game (not unlike Jenga) shows a writer with an extreme verbal dexterity and clearness of dramatic thought. Voice remains elusive and is more striking in performance than on paper, but it has one of the most effective climaxes in all of Hwang’s plays as the Woman dangles from a rope, surrounded by the sharp beauty of swirling flowers and the Man begins his first notes on the shakuhachi in the adjoining room. In 2002, Susan Hoffman directed a short film, Sound of a Voice, based on the play. Made through the American Film Institute's Directing Workshop for Women, it was written by Hoffman and Masanubo Takaynagi and starred Lane Nishikawa. The film premiered in 2003 at the Mill Valley Film Festival.

The short play As the Crow Flies, tells the story of Hwang’s grandmother’s African American cleaning woman who, it seems, had a split personality. Hwang wrote the play as an alternate companion to The Sound of a Voice for the famous Iranian director Reza Abdoh, who directed the two plays at the Los Angeles Theatre Center in 1986.

The charming story features two now archetypal Hwang characters in the role of an elderly, goind-deaf Chinese husband and wife. At this point, Hwang had mastered the dialect of American speech in the mouths of Chinese characters and many of Mrs. Chan and P. K.’s lines are cleverly constructed, not to mention blisteringly funny. The play is not often anthologized with the rest of Hwang’s work and is not mentioned by many Hwang chroniclers, but it has a magic all its own.

One thing Hwang had been impervious to at this point was a so-called “artistic failure.” It was at this point that Hwang left the Asian dialect altogether and wrote a play featuring all non-Asian characters. The result was a theatrical experiment that would free him a three year-long writers’ block. That play was Rich Relations, a comedy that returned to spiritual matters as its jumping-off point.

Set in the second living room of a large mansion in the hills above Los Angeles, the play concerns a college teacher escaping to his father’s house with his girlfriend, who happens to be his student. While there, Keith becomes the center of controversy as his aunt Barbara threatens to commit suicide unless he marries her introverted daughter—his first cousin—to improve the money flow between the families. The featured character is Hinson, Keith’s dad, who claims to have risen from the dead after a bout with tuberculosis and has since re-dedicated himself to God. Written with an eye toward Neil Simon, but still featuring moments of mysticism typical of a Hwang play, Rich Relations was more of a straight-on comedy than had been written previously.

The play was produced by the Second Stage Theatre and the director was the late Harry Kondoleon, who had had success Off-Broadway as a playwright. The cast assembled featured veteran comic actor Jerry Stiller as Hinson, the charming though never wildly successful Keith Szarabajka as Keith, and Hollywood darling Phoebe Cates, making her New York stage debut as Keith’s girlfriend Jill. Sadly, Stiller had to leave the show and was replaced by Joe Silver, who was thought by many to be miscast.

The play opened to universally negative reviews. Rich called it an “aberration that a talented writer had to get out of his system.” In spite of this, many consider Rich Relations important in that his greatest success—M. Butterfly—would largely feature Caucasian characters. I personally find Rich Relations very funny and its second act shift to mystical drama is as potent as any of Hwang’s second act interruptions from the otherworldly. The play was also important in the respect that its set featured several up-to-date technological equipment that were smashed up by the end of the evening. Rich noted it was probably the first play in New York to feature the C. D. as a prop. Rich Relations would go on to be produced with all Asian casts on the West Coast to acclaim.

The year Relations opened, Hwang had been asked by a friend if he had heard the story of a French diplomat named Bernard Boursicot and a Chinese opera star, Shi Pei Pu. Apparently, the two had carried on a twenty-year on-again/off-again affair and Boursicot was under the impression Shi had been a woman the entire time. He was wrong. The story was a scandalous headline in Europe. How could he not have known? Hwang had reasoned to himself that he must have thought he had found a “Madame Butterfly.” Hwang did not know much about the Giacomo Puccini opera Madama Butterfly, but a “butterfly” had become an Asian American term for a submissive “Oriental” woman bowing to a white man’s desires.

Hwang studied the opera, which had a libretto by Luigi Illicia and Giuseppe Giacosa and was adapted from the play by David Belasco and the novella by John Luther Long. The opera is, of course, one of the most performed operas all over the world, largely due to the unrivaled beauty of the music. Hwang saw a way to deconstruct the opera while telling a fictionalized account of the confused European man. Hwang had no interest in writing docudrama; he was writing theatrical metaphor that was going to expound upon national and international issues related to men and women, East and West. It would be the most talked-about play of the 1980s, an international success, a groundbreaking work for the Broadway stage, and would give Hwang a permanent spot in theatre history.

The play was originally conceived as a musical. But this notion was dropped early on due to what he perceived would be a lengthy process of collaboration. What was formulated was not merely a political diatribe, but an impassioned story of a tragic figure—his betrayals and deceptions as well as his sexual and racial misconceptions. The play was snagged by producer Stuart Ostrow (who had brought Pippin and 1776 to Broadway) and he sent the play to the formidable English director John Dexter, who thought it was the best play he had read in years. The play was soon on its way to Broadway and John Lithgow was chosen to play the lead role of René Gallimard. Actor B. D. Wong would go through a six-month audition for the role of Song Liling (Hwang’s name for Shi). Both actors would play roles that many would consider tour de forces and would be hallmarks of their stage careers.

The play got a terrible review in Washington, D. C., but it found its home when it moved to Broadway in 1988. The play was an immediate success and would go on to run three years. In what would be Rich’s last review of a Hwang piece, he called the play “a visionary work that bridges the history and culture of two worlds” as well as “a brilliant play of ideas.” The play was universally praised and found its way to the West End with Sir Anthony Hopkins and then, all over the world. It won the Tony Award, the Outer Critics Circle Award, the John Gassner Award, and the Drama Desk Award. It was also Hwang’s first play to be a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

M. Butterfly has often over-shadowed some of Hwang’s other plays. As with most American plays and playwrights (Arthur Miller with Death of a Salesman, Tennessee Williams with A Streetcar Named Desire), dramatists achieve some massive success and are expected to repeat the process over and over. Such a thing is impossible, and most writers become pigeon-holed by their most successful triumph and never move on. Even still, M. Butterfly propelled Hwang’s career in many different directions—the world of the musical theatre, film, television, and opera opened up to him. Hwang later created a new version of the text for its 2017 Broadway revival, directed by Julie Taymor.

Hwang’s next work for the theatre was a short play for the Actors Theatre of Louisville in Kentucky. Bondage, like M. Butterfly, has its primary concern sexual and gender stereotypes. This was perfectly dramatized in the figure of two completely disguised, clad-in-leather figures—one a dominatrix and the other a man visiting an S & M parlor. The play had more of an eye to the ‘90s and, though serious in its implications, is one of Hwang’s funniest plays.

The cast featured B. D. Wong and Kathryn Layng, an actress who had appeared in M. Butterfly and became Hwang’s second wife. The actors were not credited in the program as their true race was not to be revealed until the end of the play, when you realize they are the races of the first couple they “role-play" (through the course of the play, they portray several stereotypical racial couplings). The play was directed by Oskar Eustis and was produced in tandem with future Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks’ short Devotees in the Garden of Love under the omnibus title Rites of Mating at the 1992 Humana Festival of New American Plays. Mel Gussow, in the New York Times wrote “the author of M. Butterfly proves to be a wry observer of contemporary mores and racial stereotypes.” In 2015, a short film version, written and directed by Esquire Juachem, was released and can be streamed online.

Seeking a sophomore run on the Great White Way, Hwang’s next full-length play was the ill-fated Face Value. Hwang had been involved in an intense battle within the New York theatre community over the casting of English actor Jonathan Pryce as a central Eurasian character in Claude-Michel Schönberg, Alain Boublil, and Richard Maltby, Jr,’s musical Miss Saigon. In fact, the musical’s Broadway opening had been postponed by Hwang’s (and other’s) protests. Hwang decided to respond to this incident with what he would call a “farce of mistaken racial identity.” This would be his second project with Broadway producer Ostrow and would showcase Hwang’s musical leanings. He would write music and lyrics for a phony show-within-the-show called The Real Manchu. In the play, Manchu opens at the "Imperialist Theatre" on Broadway leading to two out-of-work Asian American actors breaking in backstage intending to ruin the show—mostly because they had been rejected for parts.

Hwang learned quickly that farce was a difficult theatrical medium. Veteran comic director Jerry Zaks had been brought into helm the project in Boston and then move it to Broadway. B. D. Wong returned to star, along with other well-respected comic actors like Jane Krakowski, Mark Linn-Baker, and Gina Torres. Rehearsals were hampered by the general confusion over whether the play would ever really work. The farcical moments were not sharp enough and the one scene that did work—a Pirandelloesque scene where the actual actors of the show stop the play to reflect on how stupid their characters are and how insensitive the play is—was not fully integrated into the rest of the show. Face Value opened in Boston in 1993 to disastrous reviews. The most damning criticism came from the Boston Globe’s Kevin Kelly, who wrote “it's not very funny, struggles to keep going, exhausts itself long before it's over and ends up sentimentalizing its own thought.” But D. C. had not stopped M. Butterfly, and with an eleventh-hour revision, Boston wasn’t seeming to stop Face Value. However, after eight previews, the producers announced the rather expensive show would not open. Though frustrated by the experience, Hwang would return to this experience in one of his greatest plays, Yellow Face.

Not to be discouraged, Hwang had a productive year in 1996 when he wrote another short for the Humana Festival—this time one of their “ten-minute plays.” The piece, Trying to Find Chinatown, has a simple set-up: an Asian American street musician confronts a Caucasian man who purports to be Asian and who is looking for his family’s home in Chinatown. The Asian man is offended while the white man reveals he was adopted by an Asian family and was therefore as much an Asian as the fiddle player.

The play furthered an idea brought up by Hwang in Face Value—that race was rather fluid. This was quite far removed from the Hwang who had written those first angsty plays of Asian America.. The play premiered under the direction of Paul McCrane and has become a benchmark of Hwang’s drama—the title would be the title of his third collection of plays, printed in 1999. Trying to Find Chinatown was adapted into a short film written and directed by Jeff Liu in 2022 and premiered as a streaming event through the Signature Theater.

Hwang’s second ten-minute play of 1996 was Bang Kok, written to be a part of Pieces of the Quilt, Sean San José’s Magic Theatre experiment in San Francisco. The play, in a largely stylized fashion, features two guys in a bar—one of whom had contracted A. I. D. S. in Thailand from a prostitute, who interrupts the action as the set breaks apart and she tells her story.

That year would also see the world premiere of his next full-length play. At the age of ten, Hwang had collected the stories of his ancestors from his maternal grandmother, who he thought was dying (she lived many years after this). Hwang’s printing of his family history became an important factor in one of his most mature plays. The story of his grandfather breaking tradition, setting up with Western religion, and un-binding his daughter’s feet was captured in Golden Child, an almost classical meditation on family and change. The historical play was book-ended by a contemporary story of a man dealing with his identity in the wake of his new family.

The play premiered Off-Broadway under the direction of James Lapine, who had made a name for himself in the commercial theatre writing and directing the Stephen Sondheim musicals Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Passion. The original version of Golden Child was deemed a bit long and loose, but Lapine’s direction gave it grace and beauty. Vincent Canby in the New York Times wrote "There is a quiet, though highly theatrical, intelligence at work in Golden Child...A play composed of many small moments of grace, which are not often seen on our stages." The production won Hwang his second Obie Award for Best Play.

Hwang took a year to continue working on the piece. Productions occurred in California and Singapore before Hwang and Lapine felt like they had finely honed the play. With more streamlined bookends and bringing the un-binding of the feet onstage, Golden Child became a diamond from the rough. The play opened on Broadway in 1998, making it Hwang’s return after a decade away from New York. The play featured Randall Duk Kim, Ming-Na Wen, Jodi Long, and a find in the newcomer Julyana Soelistyo, who wowed audiences with her portrayal of the “Golden Child,” Hwang’s grandmother.

Reviews were, overall, very encouraging. Clive Barnes in the New York Post wrote that it was “[a] wonderfully provocative play, showing a family torn apart and a civilization in flux. Polished and truly rewarding—Hwang's most sophisticated play so far.” And Mark Harris in Entertainment Weekly declared it “[a]n engaging, deeply intelligent meditation on the rewards and bitter costs of freedom and individuality.” Ultimately, the play gave Hwang his second Tony nomination, but as New York audiences had already seen the play, they did not flock to the Longacre Theatre and the play closed after a relatively short run. Golden Child remains, particularly in the individual scenes with the First, Second, and Third Wives, an exceptionally powerful play. Frank Rich maintained that it was his favorite play since he had retired from the Times in the early 1990s.

Eustis’ collaboration on Bondage had been successful and he invited Hwang to serve for a time as the Playwright-in-Residence at the Trinity Repertory Theatre in Providence, Rhode Island. Eustis paired Hwang with the Swiss director Stephan Müller and the two prepared a new adaptation of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen’s classical drama Peer Gynt. Gynt has long been both a favorite and a challenge for theatre companies, with few able to perform the original piece as written.

The intent of the project was to bring Hwang’s characteristic humor to the piece and achieve a workable length. The adaptation inserts contemporary references and rock songs into the classic tale. It also featured modernized language to tell the story of the “to-thine-own-self-be-true” wanderer. The production ran in 1998 at Trinity and was the first of only two non-musical play adaptations for Hwang. William K. Gale wrote in the Providence Journal that the adaptation was “scathingly funny.”

Hwang's last play of the '90s was one short enough to be printed on the back of a tee-shirt! For the 1999 Humana Festival, he and other major writers such as Wendy Wasserstein, Mac Wellman, and Tony Kushner contributed to "The T-Shirt Plays," printed on the back of souvenir shirts sold in the lobby. Merchandising was Hwang's wry, sardonic look at Hollywood's use of marketing and could be read a humorous take on the "project" itself.

In the early part of the twenty-first century, Asian-American playwright Chay Yew and the director Lisa Peterson, under direction from the Ma-Yi theatre company, enlisted several playwrights to contribute ten-minute pieces for an evening of plays on the Asian American experience. Hwang’s contribution to this project, Jade Flowerpots and Bound Feet, is a play about a Caucasian woman who tries to pass herself off as Asian to sell a book of fiction as a memoir. The play ends on a macabre note as the publisher takes blood from the woman to get proof of her ancestry. The Square, the collective title of all the plays, premiered Off-Broadway in 2001 under the direction of Peterson and received positive notices. Bruce Weber in the New York Times specifically pointed to Hwang’s piece, calling it “an arch spoof of intellectual predisposition and pretension.” The play was published in the 2004 edition of Best Ten-Minute Plays for Two Actors by Smith and Kraus.

In 2004, Hwang wrote a children’s piece commissioned by the famous Seattle Children’s Theatre. Czech writer Peter Sis had written a semi-autobiographical children’s book telling the story of a young boy awaiting his father’s return from travels in Tibet. The book was critically lauded, and Hwang was thought the perfect writer to translate and expand the piece into a full-length play for young audiences. Opera director Francesca Zambello staged the piece. Although some critics were skeptical of Hwang’s loose adaptation, Joe Adcock in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote, “this big, bold Red Box is bursting with possibilities.”

In 2007, another Hwang one act was produced as a part of the night of new works Ten. The show premiered at the Public Theatre, which had set Hwang off on his career over twenty years previous. Lloyd Suh directed Hwang’s contribution, The Great Helmsman, an uproarious play where the wives of Mao Zedong have a verbal sparring match as to who is the best wife of the notoriously dangerous leader of the Cultural Revolution. Smith & Kraus included it in their collection 2007: The Best Ten-Minute Plays for Three or More Actors.

A month later, the Mark Taper Forum, in association with East West Players, premiered Yellow Face, in some ways a major departure from Hwang’s previous work while still retaining his flair for crackling comic dialogue amid serious themes of identity. Long haunted by the failure of Face Value, Hwang took the experience and turned it on its head. Inserting himself as the lead character, DHH, he dramatized his involvement with the Miss Saigon protests and his attempt to get Face Value to Broadway. Going a step farther, Hwang invented a fictional story that musses even further dogmatic notions of race and identity. In the play, DHH casts (unintentionally) a white actor in the lead Asian American role in Face Value, leading to a double debacle for the struggling writer. There are also touching scenes between DHH and his real-life father Henry Yuan Hwang. Yellow Face opened Off-Broadway the following year under the direction of Leigh Silverman and featured Hoon Lee and Noah Bean in the lead roles. The play garnered his third Obie Award for Best Play and his second time as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Yellow Face has gone onto be produced internationally as well as being adapted into a two-part film uploaded to YouTube, directed by Leff Liu and featuring Sab Shimono.

Another night of ten-minute plays, The DNA Trail: A Genealogy of Short Plays about Ancestry, Identity, and Confusions, conceived by Jamil Khoury, opened under the auspices of the Silk Road Theatre Project in Chicago, Illinois on March 8, 2010. Produced in association with the Goodman Theatre, at the historic Chicago Temple Building, Hwang offered A Very DNA Reunion, a play that dealt with the now ubiquitous subject of the imprecise, but fascinating science of DNA. The play was directed by Steve Scott.

His next full-length success also originated in Chicago, winning the Joseph Jefferson Award for Best New Work. Chinglish, a play inspired by Hwang's trip to China where he noticed the often absurd translations from Chinese to English that appear on signs ("Handicapped Restroom" becomes "Deformed Man's Toilet," for example). In the play, a Westerner, who it is later revealed worked for Enron, attempts to save his family's signage business by offering to correct these problems in a relatively small Chinese province (meaning a population of six million). In trying to navigate the complicated world of Chinese business relations (and with little help from the translators), he becomes entangled in an affair with the privince's Vice Minister of Culture. A seriocomic play partly about the pawns one uses in the world of business, it has continued to delight audiences in multiple productions since. Produced first as the Goodman Theatre, and again directed by Silverman, the play had its Broadway premiere at the Longacre in 2011, when it was nominated for the Drama Desk Award.

Hwang’s most recent full-length play is Kung Fu, a play that combines dance, Chinese opera, and martial arts to tell the story of the legend Bruce Lee. The play premiered as part of an entire season of Hwang’s works (including revivals of Golden Child and The Dance and the Railroad) at the famed Signature Theatre in New York in 2014, directed once again by Silverman. The same year saw his most recent one-act, the Biblical-themed Cain and Abel. Ed Sylvanus Iskandar commissioned four dozen playwrights for a modern take on the medieval Mystery plays. Including contributions by Lucas Hnath, Craig Lucas, Dael Oerlandersmith, and José Rivera, The Mysteries premiered at the Flea Theater Off-Broadway.

David Henry Hwang is a writer who always challenges the audience. He opened the eyes of many to the struggles of Asian America. He has stood as a respected figure in the Asian community for his works that explore diversity, friction, and harmony among all peoples of this experimental country. In his honor, the East West Players christened their most recently built main stage the David Henry Hwang Theatre.

Next week, David’s adventures on musical stages…

Commentaires